Books and bad feminism

Let's talk about one of my favourite things in life (books) and one of my least favourite things in life (contemporary mainstream feminism).

To do any kind of analysis of the world of books we can start by dividing it into three main areas, or groups of people involved: writers, readers, and publishing houses. The first two groups are self-explanatory. The last group comprises all professional activity bridging the gap between the person who writes and the person who reads: publishers, editors, proofreaders, translators, marketers, etc.

What are the sex imbalances in those three areas?

Let's review some facts.

Authors

“629 of the 1,000 bestselling fiction titles from 2020 were written by women.” [Guardian 2021]

“Of the 10 best-selling books of the past decade, eight were written by women.” [Atlantic 2020]

“Women authored less than 10 percent of the new books published in the US each year. They now publish more than 50 percent of them. Not only that, the average female author sells more books than the average male author. […] By 2020 […] women were writing the majority of all new books, fiction and nonfiction, each year in the United States. And women weren't just becoming more prolific than men by this point: they were also becoming more successful. […] The average female-authored book now sees greater sales, readership, and other metrics of engagement than the average book penned by a male author.” [NPR 2023]

Women publish 3× more books (ie, 200% more books) than men in novels and fiction category:

“Within the ‘general and literary fiction’ category, 75% were by female authors – 75% female-25% male appearing to be something of a golden ratio in contemporary publishing.” [Guardian 2021]

“The dominance of women in the book trade is most apparent in fiction. […] Female novelists replaced white male authors in the 2010s” [Atlantic 2020]

It's not just that female authors are writing, publishing and selling more books than men — they are winning most of the literary prizes and awards, too:

“Vintage, one of the UK’s largest literary fiction divisions, announced the five debut novelists it would be championing this year. […] All five of them are women. But you could be forgiven for not noticing it, so commonplace are female-dominated lists in 2021. Over the past 12 months, almost all of the buzz in fiction has been around young women. […] Over the past five years, the Observer’s annual debut novelist feature has showcased 44 writers, 33 of whom were female. You will find similar ratios on prize shortlists. Men were missing among the recent names of nominees for the Costa first novel award. Here, too, the shortlisted authors over the past five years have been 75% female. This year’s Rathbones prize featured only one man on a shortlist of eight. […] The ‘paths to success’ are narrower because there are fewer prizes open to men, fewer magazines that will cover male authors, and fewer media figures willing to champion them.” [Guardian 2021]

“The big literary awards this year have been positively dominated by female writers and—remarkably—this is considered totally unremarkable. […] Women's names have been filling the literary award slates for the better part of this century.” [Atlantic 2020]

Readers

At this point, saying that boys are lagging behind in education at all levels, that men have

worse comprehension skills and verbal ability, and that men read fewer books than women should

be as commonplace as saying that women are the minority amongst

Fortune 500 CEO's — and it should spark the same level of interest

much more interest, since it's a more consequential imbalance affecting

orders of magnitude more people in the world.

And yet here we are, oblivious to the most salient biases and gaps while we wage culture wars, sometimes around minuscule differences.

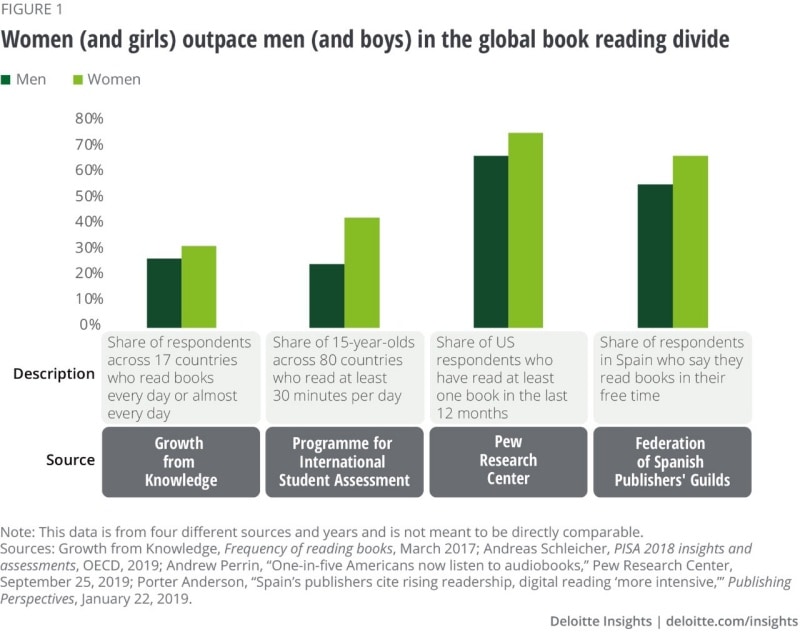

So let's state it once again: women read more, and buy more books.

“Women generally read more books than men.” [YouGov 2018]

“Women read more than men, and more novels in particular.” [Atlantic 2020]

“American women are more likely to read books than American men, especially when it comes to fiction.” [NPR 2023]

American Time Use Survey:

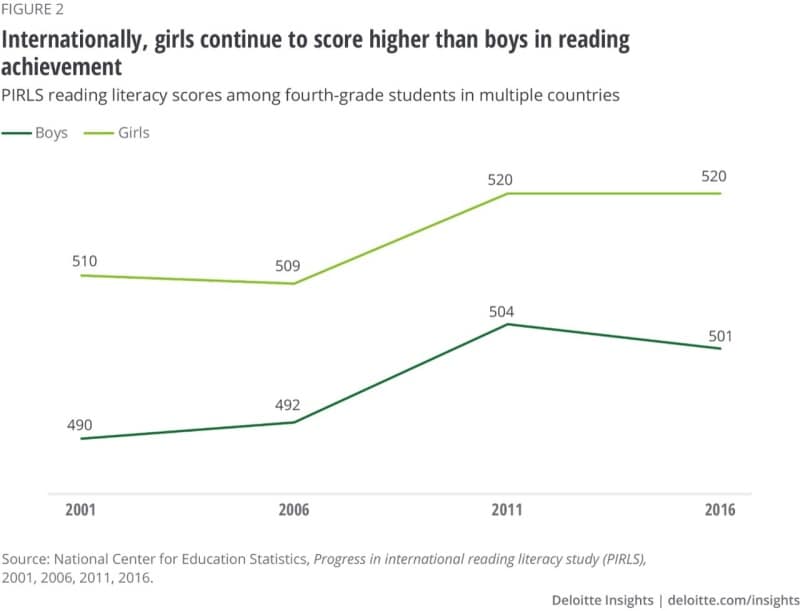

Girls and women also read better than boys and men:

Publishers

In the UK, two of every three people publishing or editing books are women:

“Of 19 editors commissioning fiction at Vintage, only four are men. […] A diversity survey, released in February by the UK Publishers Association, had 64% of the publishing workforce as female with women making up 78% of editorial, 83% of marketing and 92% of publicity. […] There is clearly a hegemony emerging in the publishing world […] which threatens to make fiction stale and predictable, as well as alienating potential young male readers.” [Guardian 2021]

As for the US, there's an even bigger gap:

“A study on the publishing industry in the United States revealed that 74 percent of employees in the field were […] women in 2019, whereas men accounted for 23 percent.” [Statista 2021]

“A survey of American publishing has found that it is blindingly […] female, with […] 78% women.” [Guardian 2016]

For comparison, 72% of members of the US House of Representatives are men, and 67% of employees at large technology companies are men. Those are smaller gaps in the opposite direction — and yet they provoke more indignation and policy discussions, and attract more public attention.

What's more: in the case of Congresspeople, that gap affects way fewer people and in a much more rarefied environment than the book-publishing industry, which employs tens of thousands of regular people. Moving the dial one percent point towards parity in the US Congress means giving four women a seat in Congress. Advancing 1% towards parity in the book publishing sector means giving jobs to 720 men in the US alone, in an industry where women are better represented and served, and more powerful, from the producers (authors) to the consumers (readers) and all the way in between.

In this state of affairs, what's a good book-lover feminist to do?

Point to these stats and more, acknowledge the gap, and promote male publishers? Ask for more prizes for male writers, parity amongst editors, visibility for aspiring male authors? Be sensitive to the stereotyping of male preferences and distinctive ways of writing?

None of that. Instead, let's zoom in on two specific book subgenres (fantasy and YA), find some anecdotal differences in representation according to the sex of the authors (by looking at two chains of book shops and one online community), and report those differences as book shops “prioritising” men under “fantasy” and “relegating” women to the “YA” section [in Spanish; see an auto translation].

Now, that's a cause worth supporting. Because the patriarchy is so very strong when it comes to books, you know?

Sigh.

As I have said before, there is no damn way to deactivate this pervasive bias.

One would reply that this specific bias (against female authors of fantasy books) might be true (flimsy as the evidence seems), but that it makes little sense to focus on such a small and contested imbalance when it's subsumed in a much larger imbalance in the opposite direction (men falling behind in everything having to do with books in any way). One would say that “feminism” means paying attention to discrimination or unjustified differences based on sex, and that in the case of the book industry, if there were discrimination of any kind, it would be obviously against males.

Our interlocutor would swiftly answer that both things can be true at the same time, and that being conscious of one injustice doesn't have to detract from our attention to other injustices (so let's keep on talking about whether “YA” sounds less glamorous than “fantasy”, and see if there are fewer women listed there).

Then, just as we concede that that is true, nothing will change, because the other side will go on ignoring the issue at large (the problems of boys and men with books) because it's awkward and doesn't fit neatly in the enlightened narrative of contemporary mainstream feminism — just as before.

[Atlantic 2020] There Is a Culture Industry That Gives Its Top Prizes to Women (The Atlantic, Jan 2020)

[Guardian 2016] Publishing industry is overwhelmingly white and female, US study finds (The Guardian, Jan 2016)

[Guardian 2021] How women conquered the world of fiction (The Guardian, May 2021)

[NPR 2023] Women now dominate the book business. Why there and not other creative industries? (NPR, Apr 2023)

[Statista 2021] Distribution of employees in the publishing industry in the United States in 2019, by gender (Statista, Mar 2021)

[YouGov 2018] How many books per year do Americans read? (YouGov, Aug 2018)

A Girl Writing; The Pet Goldfinch by Henriette Browne: Wikimedia Commons (public domain)